Video Sources 0 Views

Synopsis

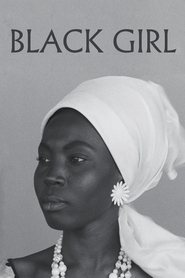

Watch: La Noire de… 1966 123movies, Full Movie Online – A Senegalese woman is eager to find a better life abroad. She takes a job as a governess for a French family, but finds her duties reduced to those of a maid after the family moves from Dakar to the south of France. In her new country, the woman is constantly made aware of her race and mistreated by her employers. Her hope for better times turns to disillusionment and she falls into isolation and despair. The harsh treatment leads her to consider suicide the only way out..

Plot: Eager to find a better life abroad, a Senegalese woman becomes a mere governess to a family in southern France, suffering from discrimination and marginalization.

Smart Tags: #inner_monologue #boyfriend_girlfriend_relationship #suicide #maid #master_servant_relationship #flashback #narrated_by_character #domestic_worker #photograph #suitcase #wig #money #france #servant #senegal #third_cinema #homesickness #nanny #post_colonialism #razor_blade #mask

Find Alternative – La Noire de… 1966, Streaming Links:

123movies | FMmovies | Putlocker | GoMovies | SolarMovie | Soap2day

Ratings:

Reviews:

Colonialism Unmasked

“La Noire de…”–better translated as “The Black Girl/Woman de…,” retaining the French preposition with its ambiguous connotations, either meaning “of” or “from” or “belonging to”–is credited as the first sub-Saharan African feature film to receive international acclaim. Its author, Sembène Ousmane is likewise considered the “father of African cinema.” Indeed, Senegal had only recently declared independence from French colonial rule in 1960, and, reportedly, before that Africans in French colonies were prohibited from making their own movies. One assumes this ban existed because the authorities feared such a thoroughly anti-colonialist picture being presented as in “Black Girl” and even more so that it be artfully composed. For, despite clocking in at under an hour (although originally a bit longer), Ousmane’s film tenders a taut thesis, subtly adorned in art and while still managing a shamefully shocking end and strikingly symbolic epilogue.If this were simply postcolonial social commentary, as admirable as that message may be, it would be easy to write off “Black Girl,” which is what the French Film Bureau did in rejecting to produce it (although, they later purchased the rights to (or not to) distribute it). It’s the crafting of the message that makes this a great film, though. I especially love the use of the mask here–a piece of African art much like the film itself that serves as a source of contention for its control, within and without the film. At first, while in Dakar, Diouana, the protagonist, offers the mask as a gift to her employers, for which they place it beside other pieces of African art decorating their villa. Back in their high-rise apartment in France, however, the mask hangs alone on the white family’s wall, with the only apparent other they take back with them from Senegal to France being Diouana. When the boy who originally possessed the mask regains it, he shadows one of Diouana’s employers, the man, as if haunting him with the history of colonialism while simultaneously deporting him from a newly free nation.

The precision of the black-and-white cinematography is worth remarking upon here, too. With a minimalist aesthetic reflecting its low budget and the influence of the French New Wave, it may be easy to miss how well the photography reinforces the social commentary. Jonathan Rosenbaum (see his book, “Movies as Politics”), for one, reiterates what another film critic, Lieve Spass, says regarding the black-and-white dichotomy of the picture in everything from the dots on Diouana’s dress, the food they consume (white rice and milk, black coffee and “Black and White” whisky), to, most dramatically, Diouana in the white bathtub. There’s also the dark mask on the apartment’s white wall, the black void Diouana stares out at from that apartment, in addition to the obvious pigmentation. When the white French woman looks over a crowd of black women waiting for work as maids, the visual connotation to a slave market isn’t lost. Nor is it when Diouana is mistreated by those she serves in France: the shrewish madame treating her as inferior, the mostly indifferent monsieur, kissed by a stranger who doesn’t bother with a request or introduction after remarking that he’s never kissed a black woman before, overhearing another guest suppose that Diouana instinctually, “like an animal,” understands commands in the French language (one may be forgiven for thinking it was the two centuries of French colonial rule that explains the people of Senegal knowing French–heck, the Normans only controlled England for half a century a millennium ago, and there remain thousands of French cognates in the English language to this day, but I digress).

It rather goes without saying that this is an economical picture, although, again reportedly, originally the film included a color sequence. In addition to the photography, however, there’s the sparsity of story and dialogue, which I admire, notwithstanding that some Westerners seem to be put off by it. Regardless, relying on Diouana’s internal narration is effective in focusing the narrative and getting the point across–that the dream and promises that led her to France becomes alienated from her confined reality, which she compares to being treated like a prisoner and slave, as others cast her as a racial, supposedly inferior “other.” Her illiteracy along with her general muteness compounds her alienation, as wrenchingly detailed in the scene involving a letter supposedly from her mother. The general English translation of the title is rather suiting in this regard, to simply label her and the film as the “Black Girl,” to not even question from whence she belongs–her identity simply stated and assumed, as her employers and the colonizers would have it. The film returns her voice, if only for the spectator, and likewise the identity of postcolonial Africa.

Review By: Cineanalyst Rating: 9 Date: 2020-02-20

From militant silence to militant voice

The simple scenario, based on a newspaper report, finds the titular character, Diouana, moving from Senegal to the South of France to take up a position as domestic for a bourgeois French couple whose business interests in Dakar are, it’s implied, waning in the post-independence moment. But the power relations within the French apartment are still very much titled in their favour-horrifyingly so-as their neglect and abuse of Diouana, withholding her earnings and preventing her leaving the apartment, see her ultimately commit suicide rather than continue in the status of property. Little under an hour in length, the spatial and temporal constriction of the film gives it at once the clarity of a fable and the brute reality of the observed. Few other films that so well to suggest space, to excavate the contours, the power relations of a series of rooms (‘Petra Von Kant’, a very different film-though, at least in its ending, it also has something to say about labour and silence-has a similar constriction, whilst seeming more ‘theatrical’). Sembène relentlessly exploits the way imprisoning social walls take place within a domestic space-the rooms of the apartment paced, evaded, sites of divided and perpetual labour in which white employees take out their frustrations on themselves and on their servant, demanding that their ash trays, their dishes, the traces of their afternoon boozing be cleared almost as soon as they’ve appeared by a worker whose human presence must be reduced at every cost. Trapped within the apartment with no way to escape, Diouana faces few options for active resistance. How can one organise a workplace when within that workplace-which is also one’s new home-one is kept entirely solitary, essentially cut off from the outside world? Diouana’s eventual acts of resistance are to reclaim the mask she’d gifted her employers in Dakar when they wooed her with promises of a cosmopolitan lifestyle and apparent personable tolerance; refusing to work even when told ‘no work, no food’; and ultimately, her suicide, the newspaper report which inspired the film. As the ambiguity of the film’s title-erased (and gendered) in its English translation-suggests, Diouana has been rendered the property ‘of’ her employers-‘Le Noir De’…’ as at once ‘The (Property) *of* (her employers)’ and ‘The (Property) *from* (Dakar, transplanted to Antibes)’. Given this, her hunger strike, work stoppage and ultimate removal of herself prevents her from becoming something to be used, even as it also removes her from the world as such. In the film’s coda, ‘Monsieur’ returns to Dakar to bring her parents news of her death, his offer of money-a kind of bad conscience pay-off-brusquely refused by her mother. The tables have not exactly turned, but as he’s followed by the child wearing the mask that Diounna had gifted her employers, which they’ve taken as a trophy of display just as they bring Diounna herself back from Dakar, his discomfort suggests the white subject no longer quite as at home in the world he surveys-even as this post-independence film strongly suggested that the official ending of colonialism had by no means solved the majority of its problems, the systems of racialised and gendered exploitation that take place in centre as well as periphery, the sharp distances that keep the two separate and invisible to each other.Such invisibility has, in part, to do with the linguistic consequences of underdevelopment-the lack of access to the written word (or, for that matter, the spoken word of the colonial powers by which so much of the economic and power relations is transacted, upheld and sustained.) Sembène, whose political career began as activist (see Billy Woodberry’s excellent recent ‘Marseilles Apres la Guerre’), thence to writing and thence to cinema, makes films because this is the only way to convey an artistic statement-by which art is meant in its fully socialised senses, not as removed domain for the edification of an already-trained class-to those who literally cannot read. Illiteracy forms a key role when Diouana’s employers read out to her the letter written by her mother-in dictation to the schoolteacher-asking for money and for news, and themselves write out ‘her’ reply with its lies of good treatment and happiness. Having had her earnings stored away from her and having been prevented from leaving her place of work, and lacking the literacy to write, Diouana has been completely cut off, doubly deprived of a voice. Diouana’s response-to rip up the letter from her mother-suggests, that as Tessa Nunn puts it, “No message is better than a message that upholds the status quo.” Likewise, after Diouana’s death, her mother’s response to Monsieur’s offer of money is simply to walk away: not denunciation, not spoken refusal (across the gap of language), but a palpable silent gesture. Sembène does not suggest that these silent gestures-the mother’s walking away, Diouana ripping up the letter, refusing work and food and then life itself-are anything like acts of resistance that have reached to the level of the collectively politicised. If cinema can depict them, literacy will enable a voice to be given to that which can only figure its defiance through a militant silence.

To move beyond such silence, Sembène insists that tools of resistance and re-education against the mendacious and continuing forms of colonialism and neo-colonialism include art, far from the ‘luxury’ it can be assumed to be within certain Western Marxist discourses. Sembène places himself to the edge of the film’s final scenes, a figure of relaxed gravitas as the pipe-smoking schoolteacher in the cheaply constructed École, a figure of authority and transmission paralleling his own conception of the role of the filmmaker. It’s the schoolteacher who writes Diouana’s families letters to her-the only means of communication they have with their daughter once she leaves the country-and he who translates for ‘Monsieur’ when he performs his exculpatory visit. Sembène the filmmaker also serves as both translator, educator, and the one who will provide the audience the means to articulate themselves, rather than through the representational projections and occlusions of others. Cinema here functions as resistance and re-education, but it also serves as access to an affective truth without which the film would be useless. The film thus depicts not only the objective grimness of Diouana’s situation but the intwined the subjective effects within her, a subjective mode that can never be articulated within the frames in which she finds herself trapped: it externalises that which cannot be externalised, tries to give voice to the experience of a person whose death otherwise occupies a few sentences of sensational newsprint, no more. To externalise requires language-oral if it can’t be written, visual, if it can’t be spoken-hence cinema.

Review By: dmgrundy Rating: 8 Date: 2020-11-09

Other Information:

Original Title La Noire de…

Release Date 1966-01-01

Release Year 1966

Original Language fr

Runtime 1 hr 5 min (65 min)

Budget 0

Revenue 0

Status Released

Rated Not Rated

Genre Drama

Director Ousmane Sembene

Writer Ousmane Sembene

Actors Mbissine Thérèse Diop, Anne-Marie Jelinek, Robert Fontaine

Country Senegal, France

Awards 2 wins

Production Company N/A

Website N/A

Technical Information:

Sound Mix Mono

Aspect Ratio 1.37 : 1

Camera N/A

Laboratory N/A

Film Length N/A

Negative Format 35 mm

Cinematographic Process Spherical

Printed Film Format 35 mm

Original title La Noire de...

TMDb Rating 7.637 84 votes